TORONTO -- When Dr. Frank Plummer talks about the first experimental Ebola drug used in an outbreak, he pronounces it "Zed Map."

"I do it consciously," says Plummer, who retired this year after serving for nearly 14 years as the head of Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg.

The rest of the world says the first letter of the drug ZMapp the way Americans do, calling the concoction of three Ebola antibodies "Zee Map." But the cocktail was created in Winnipeg and Plummer thinks the name of a made-in-Canada drug ought to pronounced the Canadian way.

Winnipeg. Half a world away from the countries in Africa where Ebola, and its viral cousin, Marburg, occasionally slip out of their animal reservoir to start infecting and killing people, as Ebola is now doing in West Africa.

They are two of the worst viruses known to humankind, as evidenced by the current outbreak, which has infected at least 5,335 people and killed at least 2,622. To date, fortunately, there has never been a case of either viral hemorrhagic fever infections within Canadian borders.

So why then is Canada's national lab an Ebola research powerhouse? Why is a facility on the edge of the Prairies, near North America's longitudinal centre, the site from whence some of the most promising Ebola research emanates?

What research? Well, there's ZMapp, the most promising of the current experimental treatments. There's also an Ebola vaccine that may be useful both to prevent infection and stop it in its tracks, if given shortly after exposure. And a mobile diagnostic lab that has changed the way outbreak testing is done.

These are enormous contributions to the scientific efforts to prevent or contain Ebola. And the fact that they come from Winnipeg seems to come down to a few good men.

------

If you ask why Winnipeg -- why Canada? -- is such a player in Ebola research, the instant answer comes in the form of two names -- Heinz Feldmann, the lab's first special pathogen's chief and Gary Kobinger, his successor and the current branch chief. They are indeed key players in the Winnipeg lab's Ebola story.

"Both of these guys are absolutely world class. I can't say enough good things about them. They are both superb scientists and in addition to being superb scientists they are great individuals," says Jim LeDuc, director of the Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch, which also employs key Ebola researchers.

"They have the right attitude. They're collaborative, they're co-operative, they share their information readily and they have a global perspective. And they know exactly what needs to be done. And they're incredibly well respected within the scientific community."

Still, the story doesn't begin with Feldmann and Kobinger.

When the federal government decided to build in Winnipeg a new, state-of-the-art laboratory to replace aging Health Canada facilities in Ottawa, it was not immediately clear the complex would contain a Level 4 lab, the high containment space needed to work on the world's most dangerous pathogens.

The Ottawa facility had not had one, meaning that any time Canada had to test a specimen that might contain a Level 4 bug, it was forced to ship the sample to the labs of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, Ga.

This was the early 1990s and concern about emerging infectious diseases was front-burner. The U.S. Institute of Medicine had issued its seminal report "Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States" in 1992. "The Hot Zone," Richard Preston's Ebola page turner, and Laurie Garrett's "The Coming Plague" were burning up bestseller lists a few years later.

"We really felt that to be properly prepared for all of the possible diseases that we were seeing spreading ... that it was better and wise for Canada to have a Level 4 lab," recalls Dr. Harvey Artsob, who was then the head of zoonotic diseases for what became the National Microbiology Laboratory, or NML, as the scientists call it.

Dr. Joseph Losof, then director general of Health Canada's Laboratory Centre for Disease Control, gave the go-ahead. The search began for someone to head the special pathogens team.

------

Lab leaders keenly wanted a young German researcher who was working in Marburg, German, but who had recently spent time at the CDC. Heinz Feldmann, who had started his career studying influenza, had moved on to researching Ebola and Marburg (the virus is named after the German town where he was working).

Feldmann was finding it tough to get the funding and support his work needed. He wanted to move on. But Winnipeg wasn't his only suitor.

"We knew we wanted Heinz. We thought he was a good fit for the lab, which he absolutely was," Artsob, who is now retired, recalls.

The lab flew Feldmann to Winnipeg to meet NML leaders. He liked what he saw, even though the first trip occurred in December. "When I came home I told my wife... 'It's bitterly cold out there.' But she said 'That's fine' and that's how I got to Winnipeg," Feldmann says.

Actually, it was not quite that easy. Artsob recalls being warned in December 1997 by LeDuc -- then at CDC and advising Health Canada on the new lab -- that Feldmann wasn't going to make the move.

"I remember Jim saying to me: 'Harvey, give it up. Heinz will not leave Europe. Heinz will not be coming.' That was my low point," Artsob says. "But in fact Heinz accepted a few months after."

"He suited Canada and Winnipeg so well."

------

NML suited Feldmann too. He liked the idea of starting his own lab, building up his own program, rather than taking over an existing one. As well, he'd been impressed by how supportive the environment appeared to be. And he was drawn to the mandate: Do science, but also do public health.

"I had the feeling that the leadership would be basically willing to put it in the people's hands, in our hands, to build this program up under the condition that we have to fulfil the public health portion of it. And that was something I learned at CDC and found very interesting, being an M.D. by training," says Feldmann, who left Winnipeg in 2008 to become chief scientist for Level 4 laboratories at the U.S. National Institute of Health's Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Mont.

Under Feldmann, the Winnipeg lab created Ebola and Marburg vaccines that are widely thought to be highly promising. Between 800 and 1,000 vials of the Ebola vaccine, called VSV-EBOV, have been donated to the World Health Organization and will be used in this outbreak, if preliminary trials show it is safe in humans. (It is effective and safe in non-human primates.)

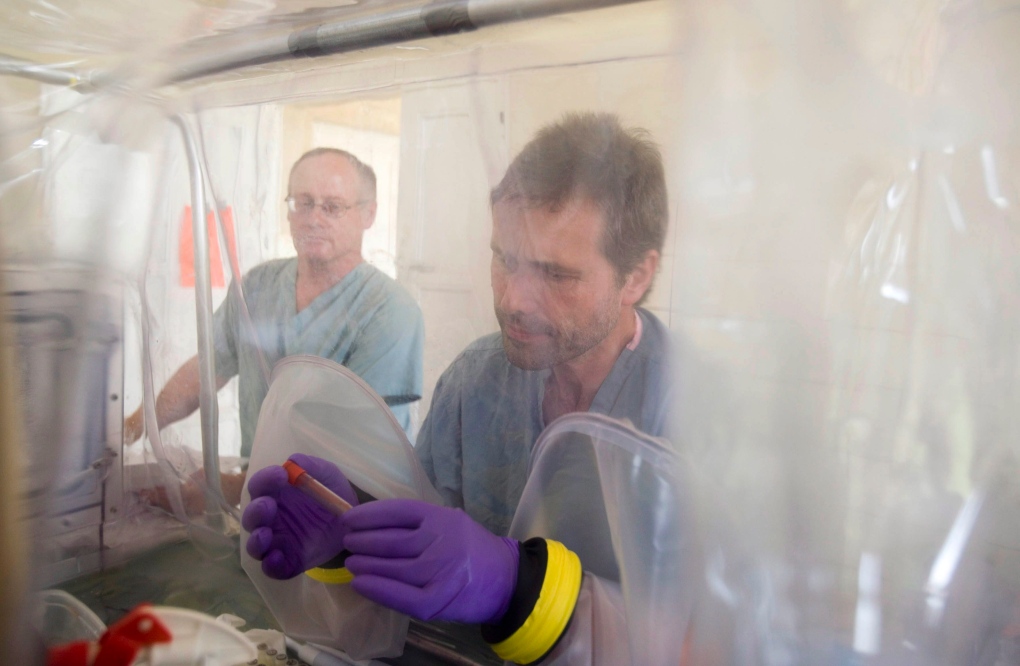

The team also created a mobile laboratory, a low-tech but safe lab-in-a-suitcase that has revolutionized how testing is done in the remote locations where Ebola and Marburg outbreaks typically occur.

Plummer says the idea originated in the uncertain days after 9/11, when anthrax-laced envelopes were mailed to news outlets and Congressional offices in the United States. Suspicious mail was found in New Brunswick, but no carrier was willing to transport it to Winnipeg. So NML had to send scientists to New Brunswick to do the testing. (It wasn't anthrax.)

The mobile lab -- and the team to run it -- was offered to the WHO during an Ebola outbreak in 2002 or 2003, Artsob says. Diagnostic testing is critical in Ebola outbreaks, because in its early stages the disease is indistinguishable from malaria and other common ailments. Figuring out who has Ebola and separating them from people who don't is how outbreaks are contained.

Prior to the creation of Winnipeg's mobile lab, the CDC took care of testing, setting up a more elaborate laboratory, generally in an outbreak country's capital. Specimens needed to be driven from affected villages to the lab, which on African roads can add hours or days to the diagnostic process.

The mobile lab could be set up where the sick people were.

"Once they (WHO) deployed us the first time I think they realized that the on site thing was giving some advantage," Feldmann says, noting that a lab technician named Allen Grolla who is still with NML was instrumental in devising the mobile lab.

The Winnipeg mobile lab has been deployed by the WHO during most subsequent Ebola and Marburg outbreaks. And many other countries have copied the model. A number of other mobile labs are in the Ebola zone helping with the current epidemic.

------

Also instrumental in Winnipeg's success was Plummer, a seasoned HIV scientist with years in the field who returned to Canada to take over as head of the new lab in 2001.

A scientist's scientist, Plummer was a Winnipeg native, eager to help his facility make a global mark.

"I think that Frank's motto is: Set your people free. And I think basically he created the environment here," says Kobinger, the rising star in Ebola research.

Says Feldmann: "I hardly have ever seen anybody that was more supportive than Frank."

"His expectations were high. But he would support any way whatsoever. It was up to you to make something out of it. You always knew you had his support -- unless you did something very stupid or something disastrous. But otherwise, you had his support."

------

Another thing about Plummer: He was always keen to bring top Canadian scientists home.

Gary Kobinger -- born in Europe but raised in Quebec -- was working on an Ebola vaccine at the University of Pennsylvania. He approached Feldmann about collaborating, and ended up splitting his time between Philadelphia and the Level 4 labs of Winnipeg.

"Heinz basically introduced Gary to me saying 'He's a really good guy, it would be great if we could find a job for him," Plummer says. "So I hired him and it was one of the smartest things I ever did."

When Feldmann was lured away to the U.S., Kobinger became his successor. "I think with Gary they found the perfect person to run that project," Feldmann says.

------

Kobinger has continued work on the Ebola vaccine. But it is with something known as monoclonal antibodies where he's made a major mark.

Our immune systems produce a soup of antibodies to protect against various invaders. But scientists try to figure out which specific ones target a given pathogen, then grow up lots of that individual antibody. Those are called monoclonals.

Kobinger and his team produced a cocktail of three Ebola monoclonals that looked promising against the virus in animal testing. Scientists at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in Frederick, Md., were also working on a monoclonal cocktail of three antibodies. There was no overlap between the two.

Kobinger decided to try to optimize the cocktails, testing various combinations to see which was best. The result: ZMapp, which is made up of two of Winnipeg's monoclonals and one made by the U.S. team. A recently published study showed the antibody cocktail protected 100 per cent of Ebola-infected primates, even when treatment was only begun five days after infection.

Plummer couldn't be prouder. "People had been trying (to make Ebola monoclonals) for years and couldn't. And we had people who were very good at making monoclonals."

------

Winnipeg's success comes down to excellent scientists given free rein to do world class work. But serendipity plays a role in science too.

Kobinger says as a scientist, he pursues avenues he hopes will work. But he acknowledges you never know until you try. Promising avenues can turn out to be dead ends.

Feldmann feels the same way.

"Out of small things and maybe being lucky -- I'm sure being lucky -- and maybe certain people making the right decisions, Canada became a player in the game. And I think that was the concept," he says.

Kobinger admits he occasionally meets people who want to know the secret of the Winnipeg lab's success.

"They're trying to understand if it's because we have more resources. I guarantee you, no," he says with a chuckle. "In relation to many labs in the U.S., definitely we have less."

It comes down to people, an institutional philosophy and support.

Plummer sums it up. "My strategy, and I think it still is the department's strategy, is to keep the scientific opportunity as rich as possible."