Manitoba children who witness intimate partner violence need more support, report finds

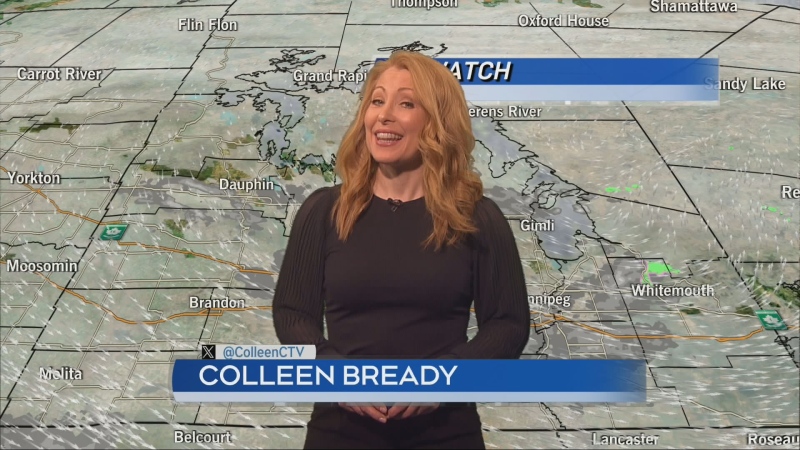

The Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth releases a report into the effects of witnessing intimate partner violence on children on June 22, 2022 (CTV News Photo Jamie Dowsett)

The Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth releases a report into the effects of witnessing intimate partner violence on children on June 22, 2022 (CTV News Photo Jamie Dowsett)

A new report on intimate partner violence is shining a light on a hidden epidemic among Manitoba kids.

The Manitoba Advocate for Children Youth found once every two hours a child in this province is exposed to violence.

In the majority of cases, they’re not getting help after being traumatized.

Ainsley Krone, the acting Manitoba Advocate, said her office examined one month of data from April 2019 and followed kids through the system after they witnessed intimate partner violence.

The advocate called the findings “deeply concerning” because in many cases, the needs and rights of children aren’t being met.

For Trevor Merasty, 23, the issue of witnessing intimate partner violence (referred to in the report as IVP) is a personal one.

“I am also a victim of IVP so this really does affect me,” Merasty said in an interview Wednesday following the release of the report. “I’ve had friends who are also victims.”

They’re not alone.

The advocate’s office examined all police-reported incidents of intimate partner violence in Manitoba for April 2019. It initially wanted to look at a whole year’s worth of data, but Krone said there were just too many incidents and neither her office nor police had the resources to compile and comb through all the information.

In the report released Wednesday, hailed as the first of its kind, the advocate found in 1,943 incidents there were children present in 18 per cent, or 342 cases. A total of 671 kids were affected; some witnessed more than one incident that month.

“The numbers really should be a wake-up call for all of us that even though we know that it’s happening…the numbers are very clear that it is a significant issue,” Krone said.

Research cited in the report said witnessing intimate partner violence can lead to cognitive and emotional impacts and behavioural problems in children. It can also translate into trouble in school, involvement in the justice system and intergenerational violence in relationships the children have as youth or adults.

“Our concern is not only that it’s happening, but the short and long-term impacts of that and how that changes peoples’ perspective of what healthy relationships are and what is normal inside of a family home,” Krone said.

Of the nearly 700 Manitoba children impacted in April 2019, 82 per cent were Indigenous.

Bill Ballantyne of Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, who serves on the advocate’s elders council, said that it is because of historical trauma.

“It is not our people that are violent, that comes from residential schools,” Ballantyne said. “I’m not making excuses for those people…but to understand where they’re coming from.”

The report also looked at what supports were received after witnessing violence.

For 36 per cent of children impacted, there was no referral to Victim Services or Child and Family Services by police.

Even if they were referred, there was no documentation of services to 416 or 58 per cent of children from either agency and if there was, Krone said it rarely included direct supports to the children. Instead, it focused on the adults.

“Which is really important but it’s not a zero-sum game,” Krone said. “Just because we’re providing services to the adults it doesn’t take away from that if we also now build up the infrastructure for the children.”

She’s making seven recommendations to the Manitoba government, including more mental health and trauma care for children because the response sometimes falls outside the mandate of Victim Services, child welfare and police.

Improvements Merasty feels are desperately needed.

“There’s no supports really for us, so it’s really hard for us growing up,” he said. “Seeing now there are more resources that are coming out, it really moves me because we needed that a long time ago.”

According to the report, CFS is automatically contacted by most police forces outside the city when they are called to cases of intimate partner violence.

The advocate said one exception is the Winnipeg Police Service. The report said its officers only contact the child welfare system if a child is in immediate danger or if charges are laid.

The WPS said it’s looking into questions from CTV News Winnipeg about its response to cases where children witness intimate partner violence but didn’t immediately provide comment.

The advocate said the report and seven recommendations have been delivered to the Stefansson government.

A government spokesperson said the findings and recommendations are being reviewed in greater detail.

“We continue to work together to help children and families in Manitoba,” the spokesperson said in an email.

“Children and youth are currently receiving supports from a wide array of resources including women’s shelters, child and family services agencies, victim services, community resource centres, youth organizations, youth hubs, schools and Indigenous-led organizations like Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata, Ka Ni Kaninchihk, N’Dinawe, as well as many other local agencies.”

The complete report can be read here.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

DEVELOPING Person on fire outside Trump's hush money trial rushed away on a stretcher

A person who was on fire in a park outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump’s hush money trial is taking place has been rushed away on a stretcher.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

'It could be catastrophic': Woman says natural supplement contained hidden painkiller drug

A Manitoba woman thought she found a miracle natural supplement, but said a hidden ingredient wreaked havoc on her health.

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

Vicious attack on a dog ends with charges for northern Ont. suspect

Police in Sault Ste. Marie charged a 22-year-old man with animal cruelty following an attack on a dog Thursday morning.

Senators reject field trip to African Lion Safari amid elephant bill study

The Senate legal affairs committee has rejected a motion calling for members to take a $50,000 field trip to the African Lion Safari in southern Ontario to see the zoo's elephant exhibit.

Tropical fish stolen from Beachburg, Ont. restaurant found and returned

Ontario Provincial Police have landed a suspect following a fishy theft in Beachburg, Ont.

DEVELOPING G7 warns of new sanctions against Iran as world reacts to apparent Israeli drone attack

Group of Seven foreign ministers warned of new sanctions against Iran on Friday for its drone and missile attack on Israel, and urged both sides to avoid an escalation of the conflict.