Manitoba First Nations leaders, advocates hope historic settlement improves child welfare system

First Nations leaders and advocates have reached agreements-in-principle with Canada over harms caused by a discriminatory and underfunded child welfare system.

It’s a system they say has resulted in high numbers of First Nations children being removed from their families and communities and placed in foster care.

A total of $40 billion has been earmarked for individual compensation and long-term reforms to improve the system.

“In Manitoba, where I come from, it’s become the epicentre of child apprehension in this country, possibly even the world and that has to stop,” said Cindy Woodhouse, Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief for Manitoba.

Woodhouse joined other First Nations leaders and federal ministers in Ottawa to unveil the details on the historic settlement.

“One that provides fair and equitable compensation to First Nations children and families harmed by discriminatory underfunding,” said Patty Hajdu, the government’s Indigenous Services Minister.

The agreements will see $20 billion in compensation earmarked for children and youth who were removed from their homes dating back to April 1991.

Children impacted between December 2007 and November 2017 by the government’s narrow definition of Jordan’s Principle, which aims to ensure equal access to publicly-funded programs, will also be eligible. So will children who didn’t receive, or, were delayed in receiving essential public services between April 1991 and December 2007.

According to the details of the settlement released Tuesday, parents and guardians may also be eligible for compensation.

It comes after the Federal Court and Canadian Human Rights Tribunal both ruled the federal government discriminated against First Nations children.

“Canada could’ve settled this case for hundreds of millions of dollars back in 2000, when we raised the alarm that First Nations kids were given 70 cents on the dollar compared to other kids,” said Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

First Nations groups and their lawyers say it’s believed more than 200,000 children and youth may be eligible for the minimum amount of compensation of $40,000 each. People who were impacted more significantly will receive more compensation.

Additionally, $20 billion over five years has been earmarked for long-term reform of First Nations Child and Family Services.

“The agreement on long-term reforms addresses the factors that lead to children being taken into care in the first place and makes sure First Nations and Child and Family Services agencies have stable and predictable funding to deliver the supports that are essential to keeping children with their families and communities,” said Marc Miller, the government’s Crown-Indigenous Relations minister.

Advocates in Manitoba said the settlement has been a long time coming.

“I was happy to hear that this investment and acknowledgment is happening,” said Cora Morgan, the First Nations Family Advocate in Manitoba. “I don’t like that it took 14 years of this tribunal to get this point where they’re committing to the resources that are needed.”

Morgan said there’s long been a lack of funding available for families for prevention, yet resources have been there for protection of children which involves taking them into foster care.

“I’ve always hoped that would be flipped where the investment would go into prevention,” said Morgan. “This agreement-in-principle earmarks funding for those prevention activities. “

Morgan said some of the children and youth eligible to receive compensation are now adults who’ve aged out of the system.

“So many of them are cast into poverty,” Morgan said. “The outcomes for children in the child welfare system are very bleak—only 25 per cent of them graduate from Grade 12. The vast majority of our homeless population have a connection to the child welfare system. A lot of people in prisons and jails were formerly in the child welfare system.”

“The majority of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls have a connection to the child welfare system.”

She hopes some compensation will be considered for some First Nations children who came into care off-reserve.

“A real reality in our First Nations is a lack of housing, so a lot of times our First Nations people move to Winnipeg and then due to poverty circumstances, their children could’ve come into care off-reserve,” Morgan said.

For a 21-year-old who can’t be identified who was taken into CFS care at three weeks old, the agreement comes with questions about whether they’re eligible for compensation because it’s aimed at children who were living on reserve.

“The catch with that is that my mother was off reserve and I’m obviously off reserve, too,” the 21-year-old said in an interview. “I’ve never even been to my home reserve.”

Canada has appealed the Federal Court’s decision to uphold the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT) ruling. David Lametti, Canada’s Minister of Justice, said Tuesday the government has committed to settling the issue at the negotiating table.

“For that reason, when we do get a final agreement it is our intention to drop the appeal,” Lametti said. “It is first in front of the Federal Court and then getting an order from the CHRT that we have met their compensation orders.”

There’s no word yet on when money will start flowing.

Lawyers involved in the agreement said the cost of administering the settlement and legal fees will go over and above the settlement amount.

Lawyers also said people can check if they’re eligible online.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

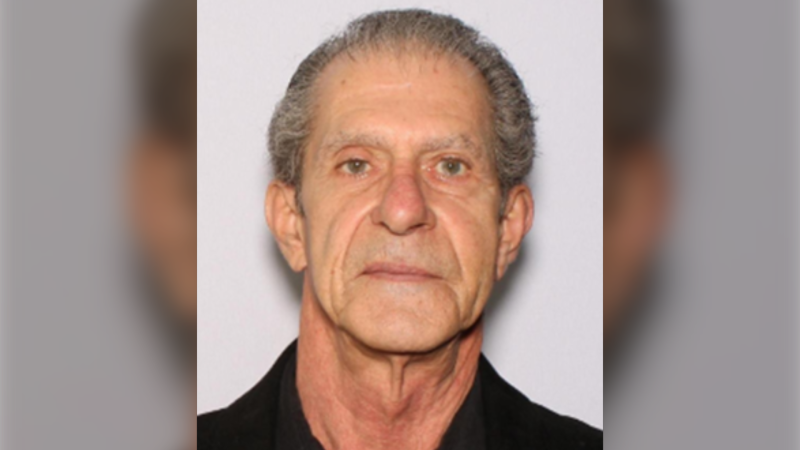

Widow looking for answers after Quebec man dies in Texas Ironman competition

The widow of a Quebec man who died competing in an Ironman competition is looking for answers.

Amid concerns over 'collateral damage' Trudeau, Freeland defend capital gains tax change

Facing pushback from physicians and businesspeople over the coming increase to the capital gains inclusion rate, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his deputy Chrystia Freeland are standing by their plan to target Canada's highest earners.

World seeing near breakdown of international law amid wars in Gaza and Ukraine, Amnesty says

The world is seeing a near breakdown of international law amid flagrant rule-breaking in Gaza and Ukraine, multiplying armed conflicts, the rise of authoritarianism and huge rights violations in Sudan, Ethiopia and Myanmar, Amnesty International warned Wednesday as it published its annual report.

Photographer alleges he was forced to watch Megan Thee Stallion have sex and was unfairly fired

A photographer who worked for Megan Thee Stallion said in a lawsuit filed Tuesday that he was forced to watch her have sex, was unfairly fired soon after and was abused as her employee.

Tom Mulcair: Park littered with trash after 'pilot project' is perfect symbol of Trudeau governance

Former NDP leader Tom Mulcair says that what's happening now in a trash-littered federal park in Quebec is a perfect metaphor for how the Trudeau government runs things.

U.S. Senate passes bill forcing TikTok's parent company to sell or face ban, sends to Biden for signature

The Senate passed legislation Tuesday that would force TikTok's China-based parent company to sell the social media platform under the threat of a ban, a contentious move by U.S. lawmakers that's expected to face legal challenges.

Wildfire southwest of Peace River spurs evacuation order

People living near a wildfire burning about 15 kilometres southwest of Peace River are being told to evacuate their homes.

U.S. Senate overwhelmingly passes aid for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan with big bipartisan vote

The U.S. Senate has passed US$95 billion in war aid to Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan, sending the legislation to President Joe Biden after months of delays and contentious debate over how involved the United States should be in foreign wars.

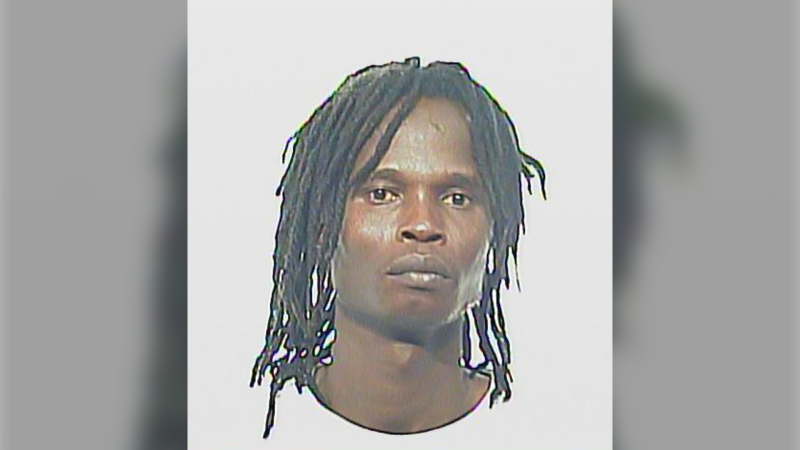

'My stomach dropped': Winnipeg man speaks out after being criminally harassed following single online date

A Winnipeg man said a single date gone wrong led to years of criminal harassment, false arrests, stress and depression.