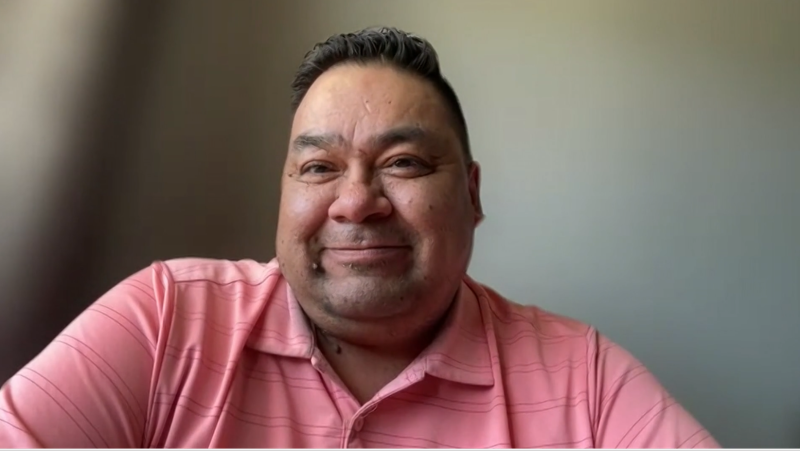

A new test designed by researchers with the University of Manitoba could help ensure patients suffering from debilitating mood disorders don’t end up with a treatment that makes matters worse.

The diagnostic test is simple and involves sitting in a chair with electrodes that measure electrical signals from the ear, said Brian Lithgow, U of M professor and lead researcher of a just-published study on the test.

“Those electrical signals are affected by the emotional, behavioural parts of the brain,” he said, explaining that the patterns in which the signals fire are different in patients with major depressive disorder than they are with bipolar patients. He said the test takes about an hour, instead of the years it can currently take to diagnose someone accurately.

“When a depressed person first comes to their first consultation, about 40 per cent of the bipolar are misdiagnosed as major depression,” Lithgow said, in part because people with bipolar disorder, particularly bipolar II, tend to “have many, many more depressive phases than manic phases.”

That means someone may grapple with only depressive episodes for years without going into a manic phase.

“For that first five years, you’ve had them misdiagnosed as major depression, because you needed that key detection of that manic phase to be able to diagnose them.

“So what we’ve been able to do is with our test, we acquire this test, and within an hour we’re basically able to measure the difference between bipolar and major depression.”

Lithgow said there are potentially serious implications to a misdiagnosis, because medications commonly prescribed for depression can be dangerous for people with bipolar disorder.

“The worst thing that can happen, if someone is treated with antidepressants, they can move from depressed to manic. And if someone has a really, really serious manic episode, they can become suicidal, or they can do something really silly like bet their house at the casino, that sort of thing.

“So it can really ruin someone’s life, a manic episode, if it’s a serious one,” he said.

Lithgow said the test wouldn’t take the place of a traditional psychiatric assessment, but would be used alongside it.

“You still critically need the psychiatrist to look after the patient, but as an adjunctive tool, I think it would be very, very useful.”

Lithgow is currently working with a PhD student to see if anxiety can also be measured the same way.

He also said more research is needed before the test could be used widely, and they are looking for investors to “finance us to run a full-fledged double blind placebo controlled trial of about 300 people,” which he said would be a crucial to getting approval from health care regulators.