New legislation which would give Indigenous communities in Manitoba a greater say in individual plans for children in care is getting mixed reviews.

An amendment to the Child and Family Services Act would allow for culturally-specific models of customary care.

Some Indigenous leaders see it as a positive move, but others say the legislation is being forced on Indigenous communities.

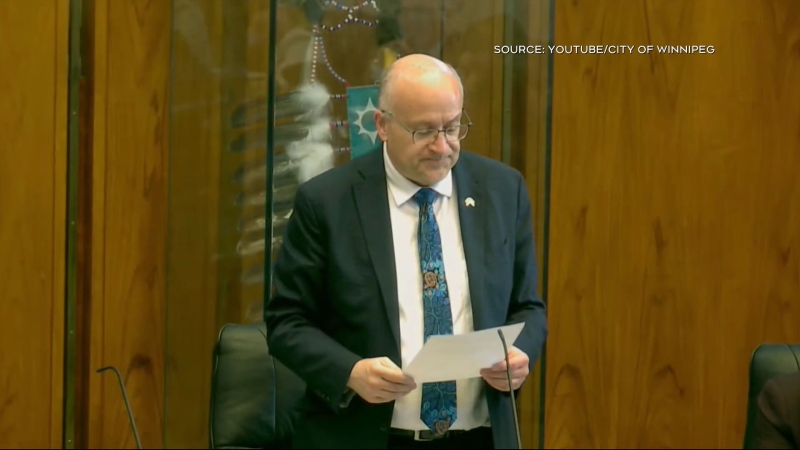

Families minister Scott Fielding unveiled some details Monday afternoon about how customary care would work.

The legislation would allow families to make a request to take children out of the existing CFS system and enter into a culturally-specific model of customary care to help maintain cultural identity and community ties.

"This takes into consideration the parents, it takes into consideration the service provider,” said Fielding. “It takes into consideration the care provider under the customary care agreement, as well, it has a parameter where the community would have a say."

CFS agencies would also be able to offer customary care to families.

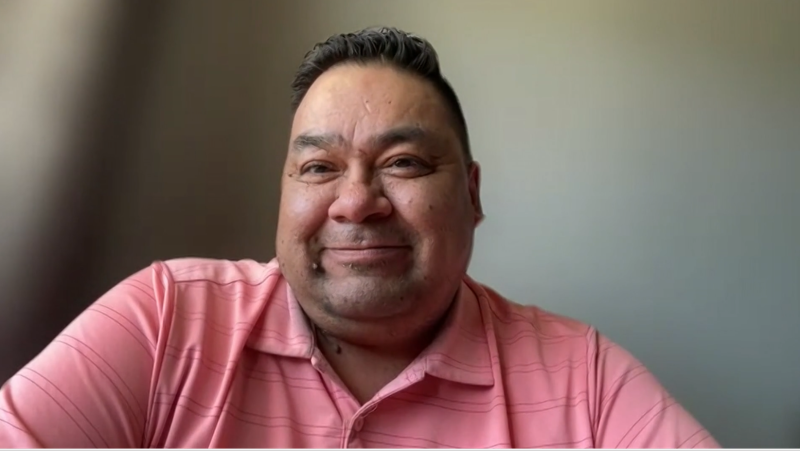

Southern Chiefs’ Organization Grand Chief Jerry Daniels supports the move.

"Customary care can allow for families and the community to be involved in what is acceptable for our children and how are we going to be responsible for that as Anishinaabe and Dakota people,” said Grand Chief Daniels.

Not everyone supports the legislation.

On the same day it was introduced, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs held an emergency meeting near Portage la Prairie on child welfare reform.

Outside that meeting, AMC Grand Chief Arlen Dumas said the current CFS system can't be fixed with provincial legislation.

“We've asked them many times, from the assembly, that we want to play a meaningful role in the development of this supposed legislation that they are ramming down today,” said Grand Chief Dumas. “Unless we have meaningful participation the legislation won’t do what they claim it’s going to do.”

Fielding said he has met with Grand Chief Dumas on numerous occasions and offered Monday to continue talking.

“We want to work with him to make a better child welfare system,” said Fielding. “That’s what we’re trying to do here.”

O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi First Nation Chief Stephanie Blackbird, member of the AMC Women’s Council, said the CFS system needs to be fixed, but she doesn’t think the legislation introduced Monday will solve the problem.

“The focus is more on apprehension than prevention, so there has got to be a lot of corrective action done,” said Chief Blackbird. “Whether it's through new funding models or when you talk about customary care…customary care means right down to the grassroots."

An overall review of the CFS system is still taking place.

A committee is expected to make recommendations to the minister in the coming months

NDP leader Wab Kinew calls the customary care legislation a good first step but has questions about resources for customary care and tracking the number of kids in care once they enter into customary care.

"Right now we know the provincial government should not be dictating the terms by which Indigenous kids are raised, but they do have a role in the conversation,” said Kinew. “We know that it’s going to take real resources to make sure that young people in customary care, in the care of CFS, can do the things that all the other children in our society take for granted, like going to school and contemplating different careers.”

Under the legislation Fielding said if the customary care provider, community, parents, and CFS agency can’t agree on a customary care plan, the child would remain in the existing CFS system.

“It takes very much into consideration different customs, cultures and teachings that are so important,” said Fielding. “Each region of the province is different and so there may be differences in terms of that approach.”

Fielding said the same safety standards that are in place for children coming into the existing CFS system will be in place for customary care