Love lost: Undelivered letters give glimpse into long-distance relationships of the fur trade

Love letters appear to be a thing of the past in the digital age.

Today, modern love arrives via text message or perhaps through a DM for the social media lovers among us.

Lines of poetry are replaced with a well-curated emoji.

However, when sending romantic sweet nothings in the age of constant cellular connection, you’re pretty well assured they will reach their desired recipient.

Centuries ago, that wasn’t the case.

A collection of letters at the Archives of Manitoba shows the thousands of miles romantic correspondence had to travel, and the many ways love could be delayed or lost altogether.

“All of these letters have one thing in common - they weren't delivered,” Kathleen Epp, keeper of the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives at the Archives of Manitoba, told CTV News Winnipeg.

The letters that make up the collection were sent from England and Scotland in the mid to late 1800s to family members, friends, or loved ones who were working with the Hudson’s Bay Company somewhere in what is now Canada.

Amelia Fay, curator of Manitoba Museum’s HBC Museum Collection says at that time, there were countless jobs throughout the expanding company. Some of the younger crew members, often recruited in the United Kingdom, spent much of their time on ships, many working on HBC’s fur trade expansion into western Canada.

“To make the trip all the way over to what's now British Columbia, they would have to go down all around Cape Horn of South America and through,” she said.

“So a lot of the employees were actually just always working on the ship, and that was their job, and then some employees were being transported to posts in this new territory.”

That meant postings with HBC could last for many years, separating countless young men from their friends, family and loved ones.

Their only connection with those back home was through letter writing at a time when paper and ink could be expensive. Letters were treasured artifacts, when today, a romantic e-mail may spend a few days sitting in an inbox, before reaching its final destination in the digital trash can.

Amelia Fay, curator of Manitoba Museum’s HBC Museum Collection, shows the long journey ships would travel to transport employees from the United Kingdom to its new western Canadian fur trade expansion in the 1800s.

Amelia Fay, curator of Manitoba Museum’s HBC Museum Collection, shows the long journey ships would travel to transport employees from the United Kingdom to its new western Canadian fur trade expansion in the 1800s.

Letters could take months, even years to make it to their destinations, and there was no guarantee they would arrive at all.

According to the book “Undelivered Letters to Hudson’s Bay Company Men on the Northwest Coast of America, 1830-57” edited by Judith Hudson Beattie and Helen M. Buss, most of the letters sent to HBC workers took the same long boat trip along ‘the Horn,’ sometimes arriving after the men had already left for home or had met with ‘tragic accidents.’

As a result, many letters remained undelivered at which point, they were sent back to HBC headquarters in London.

They, along with HBC’s records, were eventually brought to Winnipeg in 1973, and then donated to the Archives of Manitoba in the 80s.

“Archivists here opened those letters and saw them for the first time since they had been sealed up,” Epp said.

A stack of undelivered letters from a collection at Archives of Manitoba.

A stack of undelivered letters from a collection at Archives of Manitoba.

UNSEALING THE UNDELIVERED LETTERS

Editor’s note: The excerpts from the letters in this story are presented as they were originally published.

While some of the correspondence is sent from parents and siblings, there are a number from romantic interests, whose courtships were greatly interrupted or cut short altogether thanks to jobs overseas with HBC.

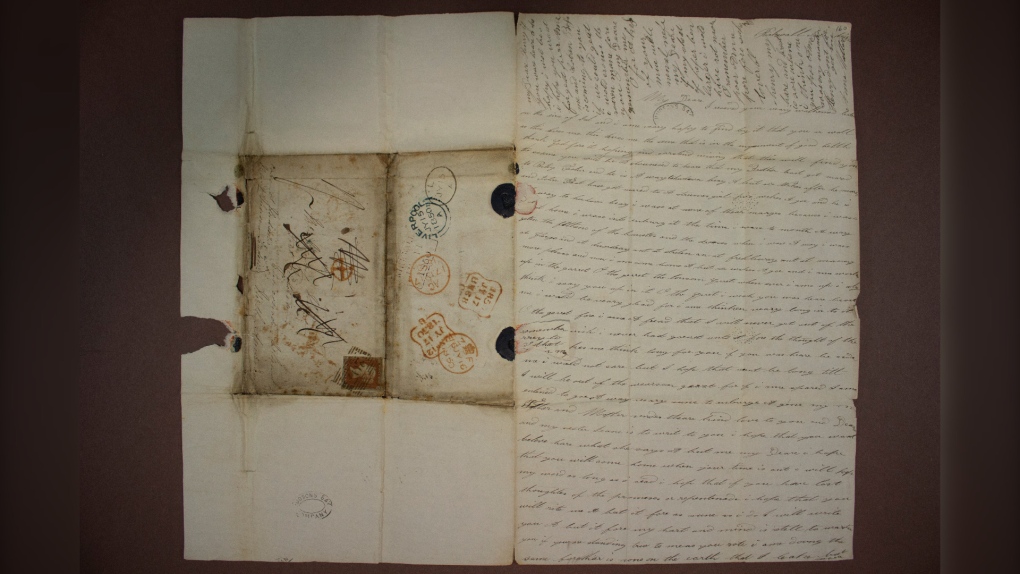

One such letter in the collection was sent by Jean Flett in Kirkwall, Scotland in November 1851 to her sweetheart Thomas Craigie.

According to “Undelivered Letters,” Craigie left Scotland at 20 years old when he was recruited to work for HBC on a ship called The Tory.

In her letter, written phonetically for a Scottish accent, Flett seems particularly hung up on Craigie and a promise he made to her before leaving town.

“Thomas you said in your first lettar that if I would keep true to you that you would keep true to me but I gust mean to tell you the truth of my mind at first which is best I think for you and me,” she wrote.

“My dear Thomas if wee should never meet on earth may wee both meet in heaven and then wee shall be both happy for eaver and eaver,” she later writes.

The original envelope used to transport Jean Flett's letter from Kirkwall, Scotland to her sweetheart Thomas Craigie in Canada in 1851 is pictured.

The original envelope used to transport Jean Flett's letter from Kirkwall, Scotland to her sweetheart Thomas Craigie in Canada in 1851 is pictured.

While spell check and modern-day punctuation would have been helpful for the young writer, so too would a more reliable delivery service. According to ”Undelivered Letters,” her love confession never reached Craigie, who appeared to work on a farming operation associated with HBC soon after, with no record of him going home to fulfill his promise to her.

He eventually married Mary Anne Porter in Victoria, B.C. in 1882 at 52 years old.

However, there are some happy endings in the collection.

Anne Watters sent her love letter from her home in Kirkwall, Scotland in July 1850 to her sweetheart Henry Horne, who was serving a four-year post in what is now Vancouver Island.

“My Dere I hope that you will come home when your time is out,” she wrote.

Ann Watters' 1850 letter to her sweetheart Henry Horne is shown in a photograph taken at the Archives of Manitoba. At the time the letter was sent, Horne was in the midst of a four-year post in British Columbia, leaving his beloved back in Kirkwall, Scotland.

Ann Watters' 1850 letter to her sweetheart Henry Horne is shown in a photograph taken at the Archives of Manitoba. At the time the letter was sent, Horne was in the midst of a four-year post in British Columbia, leaving his beloved back in Kirkwall, Scotland.

In her letter, she recalled his last drunken night in Kirkwall before he shipped off and the promise he made to her to stay true.

“I hope we will be together yet fore my hart is still on you,” she writes.

Research from “Undelivered Letters” shows she would get her wish. Horne arrived back in the United Kingdom in 1850.

He married Watters in Kirkwall two years later.

‘HAIRY’ LOVE TOKENS

Along with letters, some also exchanged love tokens as a way to have a piece of each other, quite literally, with them when they couldn’t be together.

“We have two letters where a lock of hair was included,” Epp explained.

“These letters were opened up at the archives in the 1980s, so about 150 years after they were written, there were these locks of hair.”

One was sent by Mary Anne Harrier, a fitting name, in Brixton, London to her husband John in June of 1845. The brown hair’s oily outline can still be seen on the original letter.

“I have (your letter) with the lock of your beautiful hair. Maney thanks for it. I am Glad to find it as not turned grey yet,” the letter reads. “I will send you one of my ringlets for I have a plenty of them.”

Fittingly, a woman named Mary Anne Harrier sent a lock of her tresses to her husband John in 1845.

Fittingly, a woman named Mary Anne Harrier sent a lock of her tresses to her husband John in 1845.

Century-old tresses were also found by archivists in a letter that Mary McDonald in Stornoway, Scotland sent to her sweetheart Allan MacIsaac in October 1850.

According to “Undelivered Letters,” MacIsaac was working at the Vancouver depot at the time.

Aside from her hair, her letter says she intended to send another ‘token’ of herself, but was ultimately deterred.

“I wase so bussy that I did not wait to write you with blood but I hope that is for no difference,” she writes.

Bloody valentine aside, McDonald ended up marrying another three years later.

HAPPY WIFE, HAPPY LIFE?

Not all of the letters are filled with well wishes and promises of romantic reunions.

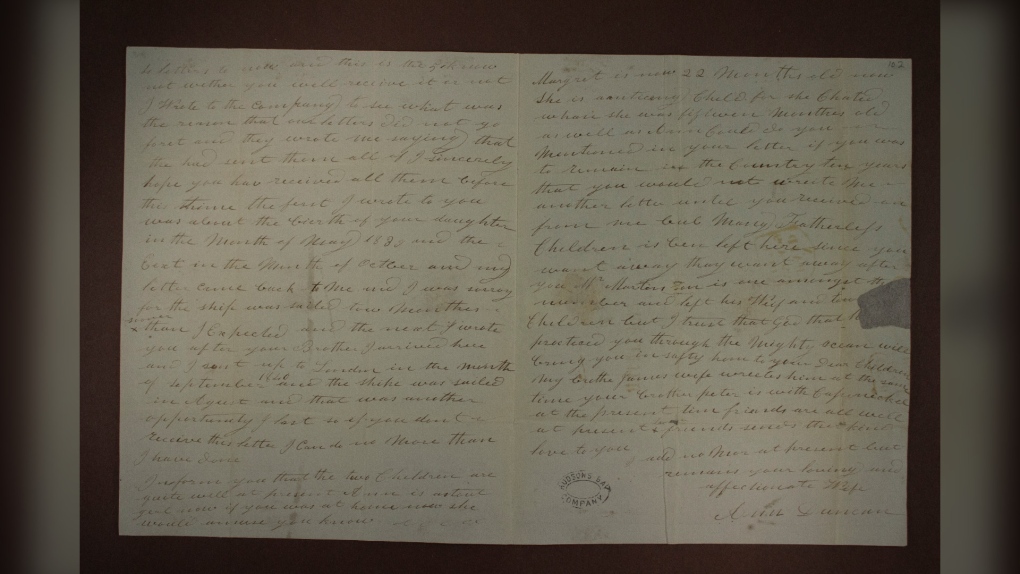

The realities of a long-distance relationship in the age of the fur trade are on full display in Ann Duncan’s 1835 letter from Kincardine, Scotland to her husband Alexander Duncan.

She writes that during their then 12-year marriage, they had only spent a mere 17 months together.

According to “Undelivered Letters,” he had signed a five-year contract with HBC, commanding several ships.

She sent five letters, and did not know if her husband received any of them. She calls his absence ‘like a dreary wilderness,’ noting he has not yet met one of their two children.

“Do you think that you don’t punish me sore enough without sending me a letter of the kien frome such a distance,” she wrote.

“You had more need to send a letter of more comfort to me.”

Ann Duncan wrote this letter in 1835 from Kincardine, Scotland to her husband Alexander Duncan, who was in the midst of a five-year contract overseas with Hudson's Bay Company.

Ann Duncan wrote this letter in 1835 from Kincardine, Scotland to her husband Alexander Duncan, who was in the midst of a five-year contract overseas with Hudson's Bay Company.

This correspondence, along with two more, are among the collection of undelivered letters at the Archives of Manitoba, showing they never made it to Ann’s husband.

However, her wish for a reunion finally came true in April 1838, when he arrived in London and continued home to Scotland.

Fay said letters such as this show the grim realities of the era.

“I don't think it's a romantic time really, at all. I think some people like to think of that ‘absence makes the heart grow fonder’ saying, but I think it would have been incredibly challenging for all parties,” she said.

“I think it would have been really stressful and sad, and so this might be a broken-hearted Valentine’s story, but that's part of the human experience, right?”

The full collection of undelivered letters can be viewed by the public at the Archives of Manitoba.

- With files from CTV's Danton Unger

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

5 rescued after avalanche triggered north of Whistler, B.C. RCMP say

Emergency crews and heli-skiing staff helped rescue five people who were caught up in a backcountry avalanche north of Whistler, B.C., on Monday morning.

Quebec fugitive killed in Mexican resort town, RCMP say

RCMP are confirming that a fugitive, Mathieu Belanger, wanted by Quebec provincial police has died in Mexico, in what local media are calling a murder.

Bill Clinton hospitalized with a fever but in good spirits, spokesperson says

Former President Bill Clinton was admitted Monday to Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington after developing a fever.

Trump again calls to buy Greenland after eyeing Canada and the Panama Canal

First it was Canada, then the Panama Canal. Now, Donald Trump again wants Greenland. The president-elect is renewing unsuccessful calls he made during his first term for the U.S. to buy Greenland from Denmark, adding to the list of allied countries with which he's picking fights even before taking office.

UN investigative team says Syria's new authorities 'very receptive' to probe of Assad war crimes

The U.N. organization assisting in investigating the most serious crimes in Syria said Monday the country’s new authorities were “very receptive” to its request for cooperation during a just-concluded visit to Damascus, and it is preparing to deploy.

Pioneering Métis human rights advocate Muriel Stanley Venne dies at 87

Muriel Stanley Venne, a trail-blazing Métis woman known for her Indigenous rights advocacy, has died at 87.

King Charles ends royal warrants for Ben & Jerry's owner Unilever and Cadbury chocolatiers

King Charles III has ended royal warrants for Cadbury and Unilever, which owns brands including Marmite and Ben & Jerry’s, in a blow to the household names.

Man faces murder charges in death of woman who was lit on fire in New York City subway

A man is facing murder charges in New York City for allegedly setting a woman on fire inside a subway train and then watching her die after she was engulfed in flames, police said Monday.

Canada regulator sues Rogers for alleged misleading claims about data offering

Canada's antitrust regulator said on Monday it was suing Rogers Communications Inc, for allegedly misleading consumers about offering unlimited data under some phone plans.