University of Manitoba researchers make surprising discovery about bird migration

This undated handout photo provided by the journal Science shows a female purple martin wearing a miniaturized geolocator backpack and leg bands. (THE CANADIAN PRESS / AP-Timothy J. Morton)

This undated handout photo provided by the journal Science shows a female purple martin wearing a miniaturized geolocator backpack and leg bands. (THE CANADIAN PRESS / AP-Timothy J. Morton)

Researchers at the University of Manitoba have made a surprising discovery about bird migration, which could help birds adapt to climate change.

Migrating bird populations have steeply declined since the 1960s with an estimated three billion lost, according to ornithologists.

Kevin Fraser, a biological sciences professor at the University of Manitoba, said researchers believe climate change is one of the main issues.

“Birds can’t keep up with the pace of climate change,” Fraser told CTV News. “That’s what our study was aimed at.”

Climate change leads to spring arriving earlier in North America, while migrating birds 9,000 kilometres away in South America are unaware of the change.

Fraser explained how insects, a primary food source for migrating birds, may already have gone through their lifecycle by the time birds return.

“The birds might be getting back too late to get the number of insects they need to raise a successful nest.”

However, the new finding from the University of Manitoba's Avian Behaviour and Conservation Lab could help migrating birds catch up to climate change.

Saeedeh Bani Assadi, a PhD student working with Fraser, found wild purple martins, a type of swallow, can be manipulated into changing the time of their migration.

Assadi hung LED light strips in the nests of wild purple martins, and, in effect, influenced the birds’ perspective of day-length.

Birds exposed to only natural light migrated south at a typical time, but researchers discovered the manipulated birds flew south later than usual.

“What [Assadi] found, amazingly, is that the birds were a little flexible to the timing of year they thought it was based on day-length,” Fraser explained.

The impact of the discovery could help influence birds to return north earlier in the spring when food supply is at its peak, and Fraser said the research could eventually reintroduce migratory birds through captive-release programs to areas where they were previously lost.

The study can be read here.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

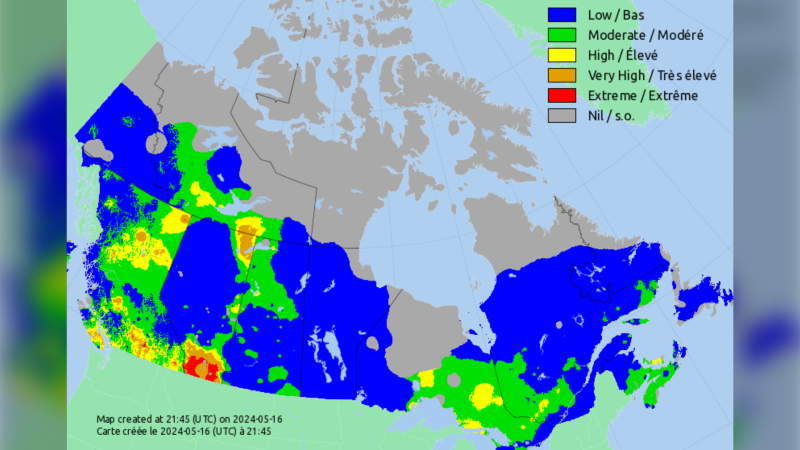

DEVELOPING 122 active wildfires burning across Canada, 32 considered 'out of control'

The 2024 wildfire season has begun, and it's shaping up to follow last year's unprecedented destruction in kind, with thousands of square kilometres already consumed.

B.C. parents sentenced to 15 years for death of 6-year-old boy

A British Columbia Supreme Court judge has sentenced the mother and stepfather of a six-year-old boy who died from blunt-force trauma in 2018 to 15 years in prison.

Veteran TSN sportscaster Darren Dutchyshen has died

Veteran TSN broadcaster Darren 'Dutch' Dutchyshen, one of Canada’s best-known sports journalists, has died. He was 57. His family says 'he passed as he was surrounded by his closest loved ones.'

'More aggressive': Tocchet shifts lineups as Canucks get ready to take on Oilers in Vancouver

As the Canucks prepare to take on the Oilers for Game 5, Vancouver head coach Rick Tocchet is making changes to the team's lineup.

Think twice before sharing 'heartbreaking' social media posts, RCMP warn

Mounties in B.C. are urging people to think twice before sharing "heartbreaking posts" on social media.

Police issue Canada-wide warrant for Regina homicide suspect

Police have issued a Canada-wide warrant for a man wanted in a homicide which occurred in Regina on May 12.

Trudeau calls New Brunswick's Conservative government a 'disgrace' on women's rights

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau assailed New Brunswick's premier and other conservative leaders on Thursday, calling out the provincial government's position on abortion, LGBTQ youth and climate change.

Kevin Spacey receives star support as he fights to get his career back

Kevin Spacey is pushing back on the 'rush to judgment' against him and is being backed by some big names as he seeks to reclaim his acting career.

Speaker cuts ties with Sask. Party, alleges he faced threats, harassment from gov't MLAs

The Speaker of the Saskatchewan Legislature Randy Weekes has severed ties with the Sask. Party after accusing some members of harassment and intimidation tactics, including a situation he claimed saw the Government House Leader bring a hunting rifle to the legislative building.