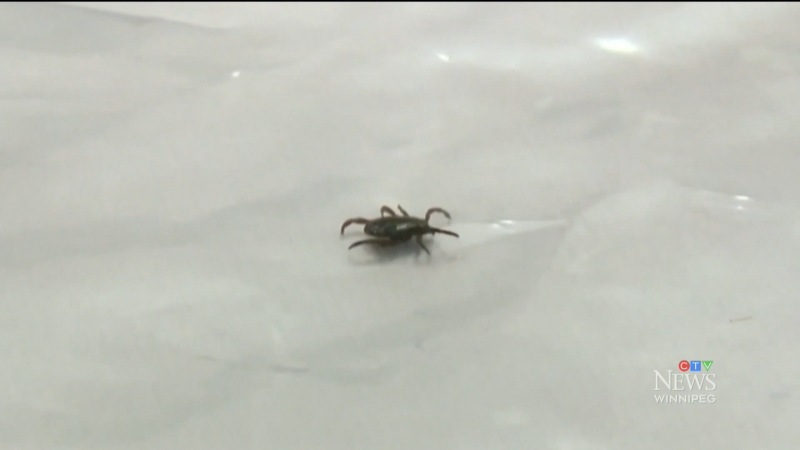

At the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre, they call the latest star attraction ‘Suzy,’ and she was 80 million years in the making.

‘Suzy’ is a mosasaur, a marine reptile that was the apex predator in the world’s oceans during the Cretaceous period.

She joins ‘Bruce’, the world’s largest mosasaur fossil on display, at the museum in Morden.

"To have both of them in a single hall that people can walk right through the middle of them, it's so spectacular,” said Pete Cantelon, CFDC’s executive director.

First unearthed as a 70 per cent complete skeleton in southern Manitoba in 1977, Suzy languished in obscurity in the museum’s fossil collection for more than 30 years before a plan was hatched to put her on display.

Frank Hadfield and a team from Alberta-based Dinosaur Discovery Studios spent thousands of hours creating plastic replicas of Suzy’s bones out of foam and plastic before painting them and assembling the complete skeleton.

"We had good representations of the whole skeleton,” said Hadfield. “Parts of the skull, vertebrae column, ribs, flippers, so that's what really excited us, to do a replication of it, that we had so much of the entire skeleton there."

Travelling through Manitoba today, most people would never imagine that it once sat at the bottom of a giant inland ocean, known as the Western Interior Seaway, that was home to some of the most ferocious predators the world has ever seen.

According to paleontologist Takuya Konishi, an assistant professor at Brandon University, the mosasaur was at the top of the food chain in the world’s oceans.

"Back in the time of the dinosaurs, those key players weren't mammals, like whales are today, but rather reptiles,” said Konishi. “And that's what makes that particular eco-system unique."

Cantelon says the fossils reconstructed from that age bring out an unmatched sense of awe and wonder in the thousands of children who visit the museum annually.

"Kids are so great, from an imaginative perspective, of being able to make things like our fossils come to life with their imaginations, so when we watch them, the same thing happens to us,” he said.

Beginning in May, the museum’s field team will be back out in southern Manitoba, searching for the next great fossil to add to their collection.