Manitoba's rich Black history preserved by community

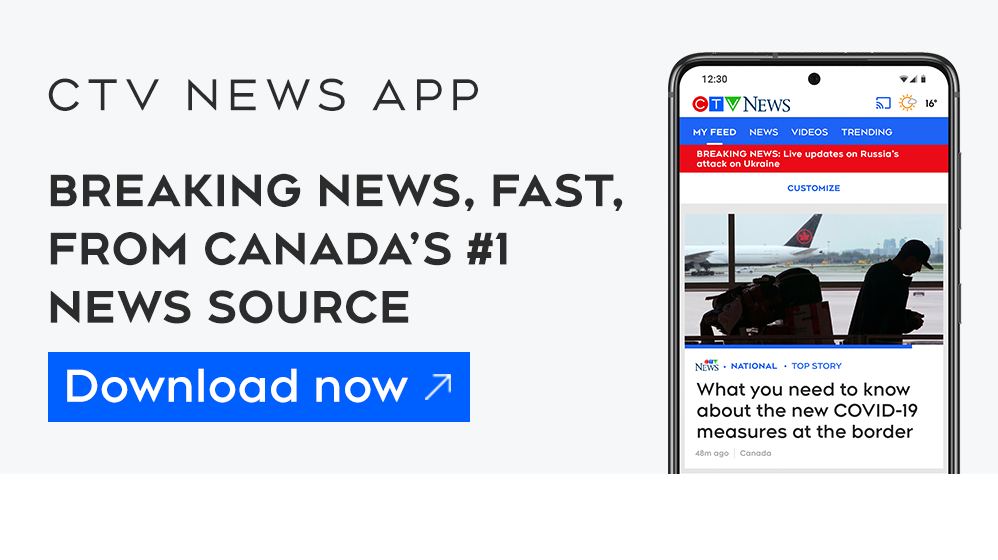

Dutch Ramsey and Marshal Gaston Jr. in front of Unity Pool Room, 1940 (Source: Patricia Clements)

Dutch Ramsey and Marshal Gaston Jr. in front of Unity Pool Room, 1940 (Source: Patricia Clements)

Three generations of Judy Williams’ family have lived, worked, or went to school in St. Norbert.

Williams’ grandmother was the only Black student at a convent in St. Norbert in the early 1900s while her mother Frances Atwell moved her family to the neighbourhood from Winnipeg’s north end.

"It seems like it's surprising that we've been here so long," said Judy Williams, whose family first arrived in Manitoba well over a hundred years ago.

At a pop-up exhibit held at the Manitoba Museum, part of a Black History Month event in February, Williams helped in teaching attendees about her family's legacy, often starting with her mother, the first Black pharmacist in Manitoba.

"It is of interest to many people," said Williams.

It’s largely fallen on members of Manitoba's Black community to actively preserve and share Black history.

Nearly thirty years ago, Patricia Clements collected the stories of many Black families in Manitoba - including Williams' - as part of a historical project commissioned by the Manitoba Museum.

"The two things that I remember of Black history that I learned from school were the names of George Washington Carver and Marian Anderson," said Clements, "Apart from that I didn't know anything about my own home province."

Around the same time in the mid-90s when Clements started her work delving into the history of Manitoba's black families, Darryl Stevenson, then a teacher with the Winnipeg School Division, led a group of twenty students in interviewing members of the Black community in Manitoba, each with a unique perspective or set of accomplishments.

"When I was attending school there was almost a complete absence of the achievements and contributions of Black Canadians in our social studies and history books," said Stevenson, adding that he wanted to be part of creating a resource on Black history for young Manitobans.

Titled 'The Black Experience in Manitoba: A Collection of Memories', the project would become a short book showcasing the personal stories, contributions and insights of forty-four different Black men and women who were living in the province. Both Stevenson and Clements' work was driven by their own desire to document and celebrate the accomplishments of Black Manitobans.

"We need to figure out a better way for some of this history to be preserved officially," said Williams.

Until then, Williams, Clements and Stevenson are taking on the roles of historians and storytellers, educating Manitobans on the province’s rich Black history.

OVER 100 YEARS IN ST. NORBERT

For more than one hundred years, Judy Williams' family has had a connection to St. Norbert and still calls it home.

Nellie Belle Johnson is pictured when she arrived in Winnipeg from St. Paul, Minnesota in 1905. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Nellie Belle Johnson is pictured when she arrived in Winnipeg from St. Paul, Minnesota in 1905. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Nellie Belle Johnson, Williams's great-grandmother, originally came with her family to Winnipeg in 1905 from St. Paul, Minnesota. The Eaton’s Company was building its mail order distribution centre for Western Canada there, and the family heard there were jobs.

In 1912, Johnson would purchase a boarding house at 298 Charles Street in Winnipeg's North End for a price of $1,400, according to a recently recovered deed agreement.

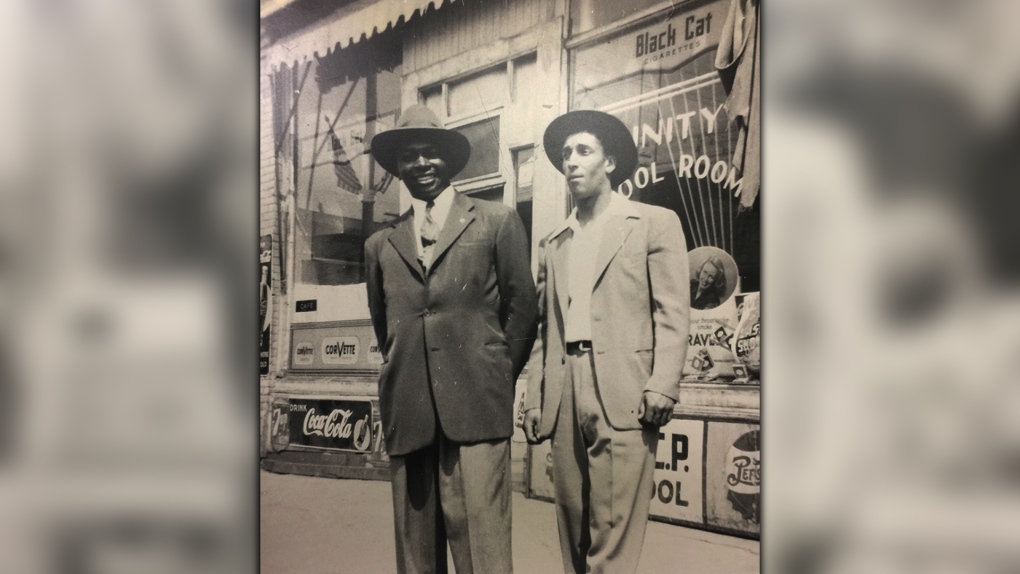

Johnson wanted her daughter, Beatrice Brown, to have a Catholic education and sent her to board at the Grey Nuns convent in St. Norbert.

"My grandmother, so the story goes, was sent on a horse-drawn buggy to the convent," said Williams, pointing out her grandmother was, at the time, the convent's only Black student in the French, Catholic boarding school.

Years later, when Williams was growing up and attending elementary school in St. Norbert, she also found herself at the same convent. From kindergarten to grade one, while Williams's school underwent expansion, her classes were relocated to the site.

"I actually shared the same space as my grandmother. I always thought that was really cool," said Williams.

Students at St. Norbert Girls' Boarding School in 1907. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Students at St. Norbert Girls' Boarding School in 1907. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Beatrice Brown was very involved in Winnipeg's North End community, running a local Girl Guides company that Black girls could join, says Williams. In 1933, she married Ernest Charles Brown, from Denver, Colorado who worked in Canada as a railway porter. Williams' grandfather was similarly active in the community, joining and eventually leading an Elks of Canada order in Winnipeg.

In 1923, Brown gave birth to Williams' mother, Frances Atwell (nee Brown). The family lived at 298 Charles Street at the corner of Redwood in north Winnipeg. There they attended the Pilgrim Baptist Church, a hub for Winnipeg’s Black community at the time.

In her youth, Atwell developed an early passion for singing - largely thanks to her mother's love of music, an accomplished piano player herself. She would go on to be a notable classical singer in Winnipeg, performing at church-related events and weddings. Atwell would also sing professionally on Winnipeg airwaves and won the Rose Bowl singing festival one year.

A group enjoys a picnic at Canora Park along the Red River in Selkirk around 1920. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

A group enjoys a picnic at Canora Park along the Red River in Selkirk around 1920. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Science, however, overcame singing when Atwell was thinking about higher education.

While in high school, Atwell worked an after-school job at a local drugstore. A pharmacist working at the store took interest in Atwell and suggested a path in pharmacy, also outlining the courses she would need to take.

Not long after, Atwell rearranged her schedule completely and eventually applied to the University of Manitoba's Faculty of Pharmacy.

A helpful neighbourhood pharmacist would play a role in Atwell's eventual career. When she was considering higher education.

A procedural delay in the faculty accepting Atwell's application turned into an opportunity for Atwell. While Atwell's academic endeavours were put on hold for a year before her application could be reprocessed, she then took up a position at St. Boniface Hospital's Pharmacy Department, hired on to work with one of the hospital's first female pharmacists.

Once Frances Atwell started university, she took a part-time position at Euclid Pharmacy, named after the street it was on and owned by Bernard Safrin, a respected member of Winnipeg's Jewish community. Graduating in 1948, Atwell became Manitoba's first Black pharmacist after a short job search she credited to Safrin.

In 1953, Frances Brown would marry George Ivan Henry Atwell, a university student from Trinidad and Tobago. George would become an influential teacher, naval officer in Canada’s reserves (reaching the rank of Lt. Commander), a professional beekeeper and a playwright.

The couple would eventually move to St. Norbert and raise their seven children, including prominent Winnipeg musician Gerry Atwell.

While Gerry Atwell's musical career and contributions to the Winnipeg community are numerous and well known, Williams credits her brother for continuously researching and sharing their shared family history with the public, a task she has "taken the mantle" of since her brother's death in 2019.

THE IMPORTANT WORK ACHIEVED BY PORTERS

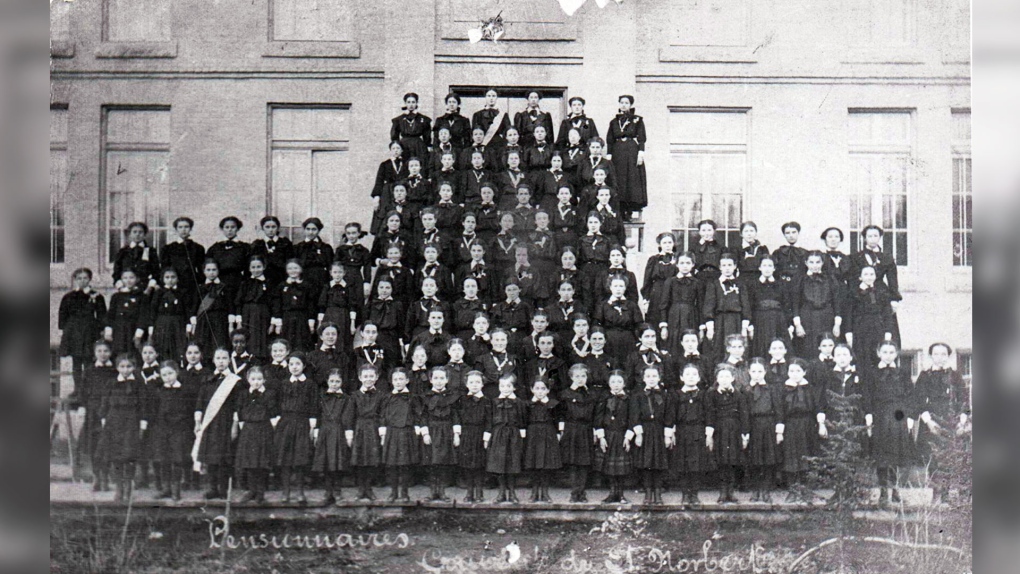

Winnipeg experienced an influx of new Black families in the 1950s, largely due to employment opportunities. Young Black men and their families moved from eastern and western Canadian provinces, or immigrated from outside the country to take up work on Canada's rail lines.

Employment opportunities for Black men were fairly limited at the time and working as a porter for the Canadian National Railway (CNR) or Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was seen as a stable job with relatively high pay.

A photograph of a sleeping car porter in 1938 in Winnipeg. (Source: Patricia Clements)

A photograph of a sleeping car porter in 1938 in Winnipeg. (Source: Patricia Clements)

Patricia Clements's father was one of many Black men who took a job as a porter, moving the family from a small Nova Scotia town to Winnipeg in 1951. Clements was eight years old at the time.

"Coming to Winnipeg was, in some ways, like coming to a foreign country in some ways because I had to adapt to city life," said Clements. "At that time I had no idea about segregation."

Unfortunately, segregation was a fact of life for railway Porters, one of the only positions available for most Black men at the time, even for those with higher education. Porters could not be promoted to any other position, underwent harsh working conditions and could easily be fired for even a minor complaint made by a passenger.

"If there was a complaint against a worker they could go directly to the higher officer," said Clements, who interviewed former porters (including her own father) for the "Backtracks to Railroad Ties," exhibit unveiled in 1994.

"My father had that experience and he said, "just decide if you're going to fire me or not because I’m not coming up here anymore for some petty complaint,'" said Clements.

"That was an eye-opener," said Clements. "Many of the Black community didn't venture out beyond the railroad where they were employed... because it was hard to get housing, and a good part of that was just discrimination" Working conditions for porters would eventually improve, thanks to community organizing taken up by the porters themselves. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), a workers’ union, was founded in Winnipeg in May 1945, leading to immediate improvements in pay, benefits and working conditions.

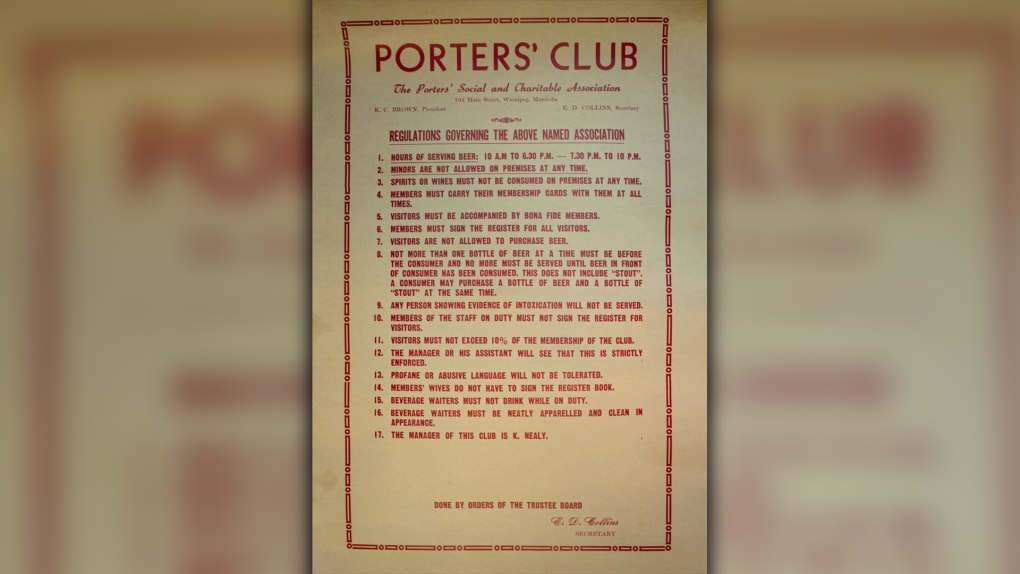

A photo of the regulations for the Porters' Social and Charitable Association, based in Winnipeg. (Source: Darryl Stevenson)

A photo of the regulations for the Porters' Social and Charitable Association, based in Winnipeg. (Source: Darryl Stevenson)

The issue of promotions for Black men, however, wasn't resolved until 1953 when the BSCP filed a complaint with the Federal Department of Labour. A year later, a complainant in the cast, George C. Garrayway, became Canada's first Black Canadian train conductor.

Clements credits the work of the porter union in breaking down barriers for Manitoba's existing Black community and for any other Black person entering the province.

"Certain people stand out for being the first bus driver, first pharmacist," said Clements," A series of 'first, first, first' because all of a sudden there were a few more choices."

None of this history was taught to Clements in school. If not for her own research, some of these stories, like her father's working experiences, would not have survived across generations.

"It's kind of an odd experience when trying to find out more about my own community," said Clements, "Apart from the curiosity I was upset because I began to understand why things happened the way they did to our community and why we were so secluded in some ways."

MANITOBA’S FIRST LOCALLY ELECTED BLACK POLITICIAN

J.R. Stevenson also worked as a porter for CNR and Via Rail, first arriving in Winnipeg in 1949. It was work Stevenson enjoyed despite poor early working conditions. He would work as a porter for over 30 years, eventually becoming the In-Charge-Porter on the Churchill line.

All that time on the rails, however, forced J.R. Stevenson away from home for several days if not a full week at a time. That left Inez Stevenson, his wife, to care for their four young boys alone.

Inez Stevenson, first Black woman to be locally elected in Manitoba, is pictured during her participation in military exercises as a member of Canada's Reserve Militia. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Inez Stevenson, first Black woman to be locally elected in Manitoba, is pictured during her participation in military exercises as a member of Canada's Reserve Militia. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Inez Stevenson did just that, while still finding time to be an active member of Winnipeg's Cari-Cana Organization (her parents hailed from Barbados and St. Vincent), participate in military exercises as a member of Canada's Reserve Militia, and helping to launch several important educational programs within the Winnipeg School Division.

"That was just the way she was," said Darryl Stevenson of his mother. "It was all so seamless."

Inez Stevenson's work to improve Winnipeg's educational system continued for many years and, in 1974, she was elected to serve as trustee for the Winnipeg School Division.

She was the first Black woman to be locally elected in Manitoba and one of the first to be elected in Canada at-large.

"When you capture what she did in her life, how truly significantly she contributed to the province of Manitoba, and in particular in Winnipeg, it's pretty amazing," said Darryl Stevenson.

"Only when I was older I realized the significance she had on the Black community in Manitoba."

Inez Stevenson served as a school trustee on the Winnipeg School Board until she died in 1981.

Harold Marshall, then a communications officer for the Winnipeg School Division, wrote a tribute to Stevenson at the time of her passing, reading, in part, "She was a stout defender of those she felt may have been discriminated against, and would take the offensive to ensure their right of privilege was safeguarded."

"Her seven years as a school trustee... is a permanent testimony to her unique character."

A photo of Inez Stevenson, first Black woman to be locally elected in Manitoba to be a school trustee. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

A photo of Inez Stevenson, first Black woman to be locally elected in Manitoba to be a school trustee. (Source: Western Canada Pictorial Index via Darryl Stevenson)

Inez Stevenson's passion for teaching and working with youth carried on across generations, with her son Darryl becoming a teacher and later principal in the Winnipeg School Division.

During his time as an educator, Stevenson realized there weren't a lot of educational resources to provide students on the contributions and historical significance of Black Manitobans or Canadians.

So, in 1993, when working as a teacher at St. John's High School, Stevenson along with colleague Patricia Graham proposed the idea of a student-led project that would collect the stories of approximately 40 Black Canadians and showcase their contributions to Winnipeg and the province at-large.

The result was the book, “The Black Experience in Manitoba: A Collection of Memories.”

“Creating and publishing a book of such historical significance took a lot of time and effort involving many people and a variety of agencies and organizations,” said Stevenson.

All that work paid off, says Stevenson, adding that when he runs into former students that took part in the project they tell him how it made a huge impact on them, even after thirty years.

"They had the opportunity to meet people in the Black community they wouldn't otherwise have met and they learned we have more similarities than differences."

STILL MORE WORK TO BE DONE

In modern Manitoba society, there are many available resources to learn more about Black history in the province. During his time as a teacher, Darryl Stevenson saw how over time Black history became better integrated into school curriculums and not relegated to February.

Still, Stevenson notes there is more work to be done.

"There are so many stories to share that would impact, significantly, on how our young Black youth would feel about themselves," he said.

Stevenson suggests a series of books like "The Black Experience in Manitoba," which would better capture the diversity of identities that make up Manitoba's Black community.

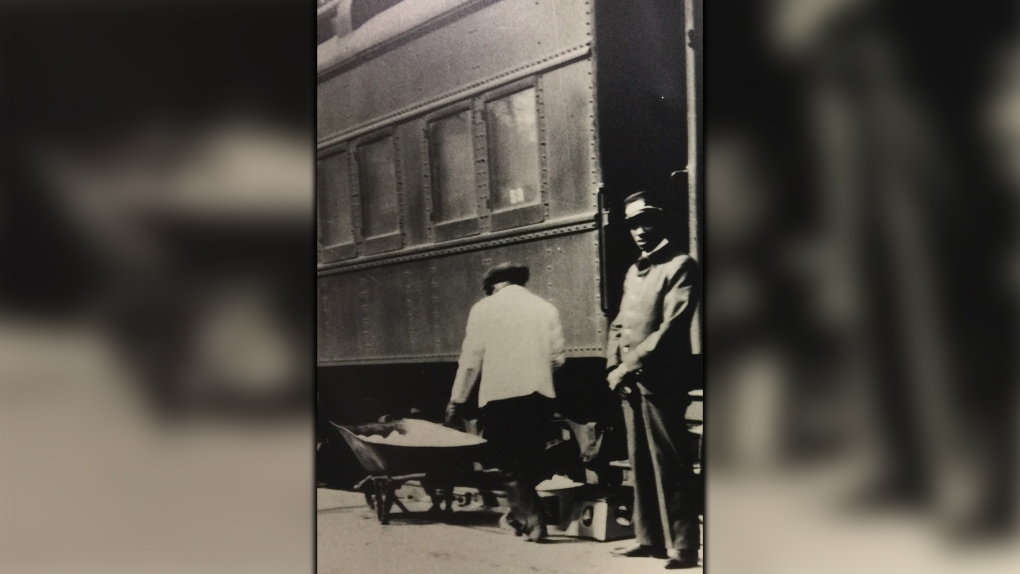

Jessie Hobson and Jim Stevenson at the Pilgrim Baptist Church in Winnipeg, 1993 (Source: Patricia Clements)

Jessie Hobson and Jim Stevenson at the Pilgrim Baptist Church in Winnipeg, 1993 (Source: Patricia Clements)

Patricia Clements agrees, especially since Winnipeg is now home to many more immigrants now compared to 30 years ago.

"I believe a similar project should be expanded," said Clements. "Lots of families in the city now weren't involved because they weren't in the Manitoba community yet."

Williams suggests an approach that is less centred on past accompaniments for one that is more forward-looking, while also acknowledging the important work Black people in Manitoba are doing today.

"That's a message I would like people to understand," said Williams, "We've been active in trying to build this city (and) trying to make life better for our neighbours, friends and families."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

The world begins welcoming 2025 with light shows, embraces and ice plunges

From Sydney to Vladivostok to Mumbai, communities around the world have begun welcoming 2025 with spectacular light shows, embraces and ice plunges.

Poilievre's Conservatives end 2024 hitting long-term high in the polls amid Trudeau resignation calls: Nanos

Pierre Poilievre's Conservatives are closing out 2024 hitting a new long-term high in ballot support, with a 26 point advantage over the Liberals amid calls for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to resign.

Female victim in Calgary double homicide identified as elementary school teacher

Rocky View School Division (RVSD) on Tuesday identified the woman who was murdered Sunday night in Calgary as Ania Kaminski, an elementary school teacher in Cochrane, west of the city.

Trump says he is planning to attend Jimmy Carter's funeral

U.S. president-elect Donald Trump said Tuesday that he's planning to attend the funeral of former president Jimmy Carter.

What Canadian game show did Alex Trebek host in the 60s? The answer continues to inspire students today

For nearly 60 years, the national Reach for the Top competition has been putting the wits of Canadian students to the test. In 2024, students from about 500 schools across the country participated in the competition.

Telegraph Cove, B.C., fire takes out beloved businesses, parts of boardwalk

The most iconic portion of a picturesque boardwalk in Telegraph Cove, B.C. was destroyed by fire on Tuesday morning.

One arrested following terrifying road rage incident on Hwy. 11 in northern Ont.

Ontario Provincial Police are asking for the public's help in investigating a road rage incident Monday on Highway 11 near Temiskaming Shores.

Nearly all of Puerto Rico is without power on New Year's Eve

A blackout hit nearly all of Puerto Rico early Tuesday as the U.S. territory prepared to celebrate New Year's Eve.

Woman burned to death inside New York City subway is identified

The woman who died after being set on fire in a New York subway train earlier this month was a 57-year-old from New Jersey, New York City police announced Tuesday.