WINNIPEG -- The family of a man who died during a 34-hour wait in a hospital emergency room is asking Manitoba's highest court to rule his charter rights were violated.

Lower court judges have previously struck down the heart of the family's lawsuit by ruling that Brian Sinclair's charter rights died with him.

But lawyers for the family argue it's "cruelly ironic" that a man who died because he didn't receive the care due to him under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms isn't allowed to sue because he is dead.

They are asking the Court of Appeal to overturn the lower court rulings and allow the crux of the lawsuit to proceed.

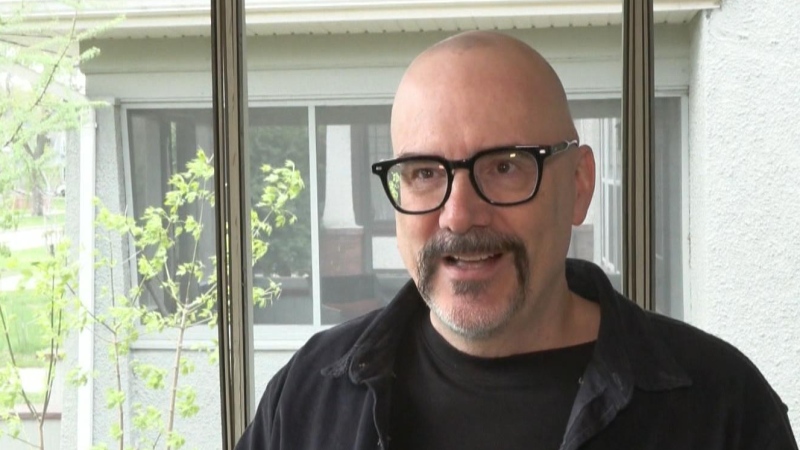

"The implication ... is that nobody can vindicate Brian Sinclair's right to life and other charter rights precisely because Brian Sinclair has been deprived of his right to life contrary to the charter," Sinclair family lawyer Murray Trachtenberg wrote in his notice of appeal.

"This is intolerable in a society governed by the rule of law. The charter should not be interpreted in a way that would preclude holding a state authority accountable."

An inquest into Sinclair's death wrapped up in June and a judge's report is expected by the end of the year.

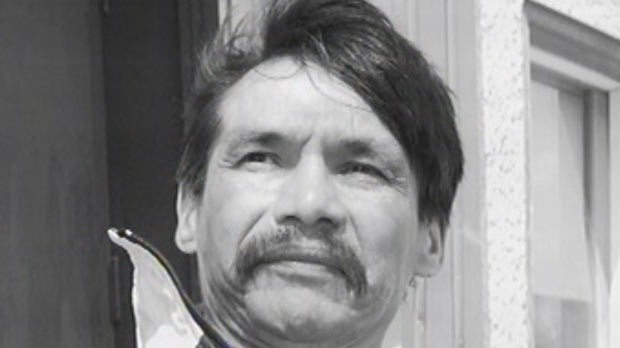

Sinclair was referred to the emergency department at Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre in September 2008 because he had a blocked catheter. The inquest heard the 45-year-old double amputee wheeled himself over to the triage desk and spoke to an aide before guiding his wheelchair into the waiting room.

There, he languished for hours, growing weaker and vomiting several times. But he was never asked by medical staff if he was OK or if he was waiting to be seen by a doctor. By the time he was discovered dead 34 hours later, rigour mortis had set in.

The province's medical examiner found Sinclair died of a treatable bladder infection caused by the blocked catheter.

Sinclair's family initially sued the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, individual employees who were on duty the weekend Sinclair died and the government of Manitoba. The family has since dropped its action against the province.

The appeal raises important points about the law and it is "critical that the action be allowed to proceed," Trachtenberg argued. He pointed to a recent ruling by British Columbia's Supreme Court which involved a father arguing for the charter rights of his deceased daughter.

"It is not 'plain and obvious' and 'beyond doubt' that there is no cause of action," Trachtenberg wrote. "There is a reasonable chance, if not a likelihood, that the plaintiff's claims will succeed and it would be unjust to summarily deprive the plaintiff of the opportunity to find justice and accountability in these tragic circumstances."

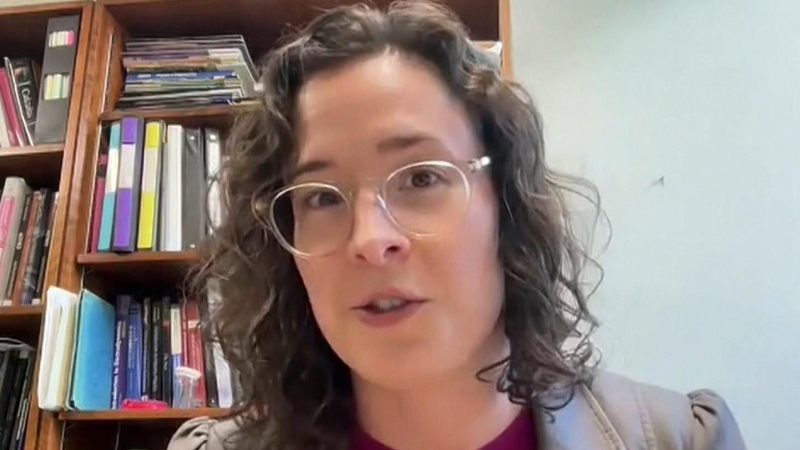

Kelly Dixon, a lawyer representing the Winnipeg health authority, said she couldn't comment in detail on what she will say before the Court of Appeal. But the health authority and the province have previously argued that the law is clear -- the Charter of Rights and Freedoms doesn't allow relatives to pursue a claim on behalf of a deceased person.

"It's really just a repeat of the same arguments," she said.

The health authority has paid out $110,000 in damages to the Sinclair family "to settle a portion of the lawsuit that dealt directly with the family's claim for loss of care, guidance and companionship for his wrongful death," the authority said in a 2012 court hearing.

If the appeal is denied, Sinclair family lawyers say they can still pursue the health authority for costs incurred by his relatives for participating in the inquest, as well as for compensation for pain and suffering caused by his death.

The appeal is scheduled to be heard Sept. 22.