A Winnipeg woman is abandoning her home, as she tries to manage a controversial sensitivity condition.

Marie LeBlanc, 51, lives with Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. The condition makes her confused and causes her to be extremely sensitive to the environment around her.

LeBlanc reacts to mould, perfumes, pesticides, and other chemicals, which most people tolerate without adverse effects.

“Confusion is a big one. You go into a building and everything is bothering you. The lights, the perfumes, everything, it affects circulation,” said LeBlanc.

Wearing a protective suit, with goggles and a breathing mask is the only way LeBlanc is now willing to step into her apartment. The suit helps stop reactions.

“There for are micro toxins due to mould,” LeBlanc said.

After living in her apartment for three years, she's moving out and doesn’t have a permanent place to go.

“It's frustrating because I feel like I'm running into barriers everywhere I go. It's like nobody knows what to do.”

Not everyone with MCS reacts the same way.

Rob Dickson, clinical team lead with Integrated Chronic Care Service in Nova Scotia said MCS is a chronic condition, impacting about three per cent of Canadians.

He said it’s generally seen between the ages of 30 and 50. Symptoms include dizziness, nausea, cognitive problems, such as memory loss, headaches and breathing problems.

Dickson said many patients coping with extreme sensitivities tend to face financial and housing hardships with little community support.

Dickson said MCS is not recognized by the World Health Organization, or in several parts of Canada, as a medical condition.

"The big reason why it's controversial is because there's little evidence that can support the diagnosis,” he said.

Dickson said many mainstream conditions can be diagnosed through a medical test, blood work, CT scan, and or MRI. However, MCS does not have a test in order to make a diagnosis.

In 2011, LeBlanc travelled to ICCS – formerly known as the Environmental Health Centre – in Nova Scotia for her diagnosis and discover how to manage the condition.

Hope for a home:

The Manitoba Human Rights Commission recognizes Multiple Chemical Sensitivity as a disability, but there's no guarantee laws can help LeBlanc.

Since late spring LeBlanc slept in a tent, and stayed with family and friends to avoid her apartment.

LeBlanc said she hasn't been able to find a suitable chemical-free home.

The commission said there is a legal obligation for employers and landlords to assess, if reasonable accommodation can be made.

"The principles that underlie the duty to accommodate, and the landlords have that duty, require the landlord to talk about the need, to get some more information and make an assessment, and sometimes it may be unreasonable to accommodate a person's needs, but sometimes that they can do something, and it may not be exactly what the person is asking for but it might still be reasonable" said executive director Isha Khan.

LeBlanc said her doctor is helping her find a place, so she doesn't end up on the street.

Making a statement about MCS:

Earlier this year LeBlanc used her talents to make a statement about MCS.

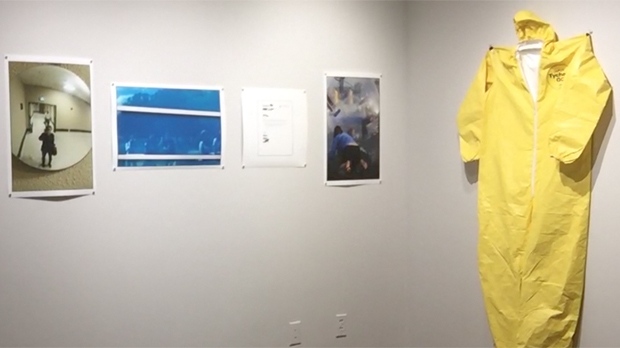

Letters from doctors and her photography was part of an exhibition on her struggle. Each piece of art is reflection on her unique perspective

LeBlanc never attended the show. She said there were too many chemicals inside the studio, and spoke with visitors using a computer.

"Martha Street Studio was so awesome,” said LeBlanc. “They were the opening amongst the world filled with barriers … I was welcomed with open arms. I was accepted. I wasn't judged."

(Photo source: Marie LeBlanc)