Around the time Candace Derksen went missing, the man accused of her murder had walked away from police custody and was living with his 14-year-old girlfriend, court heard on Friday.

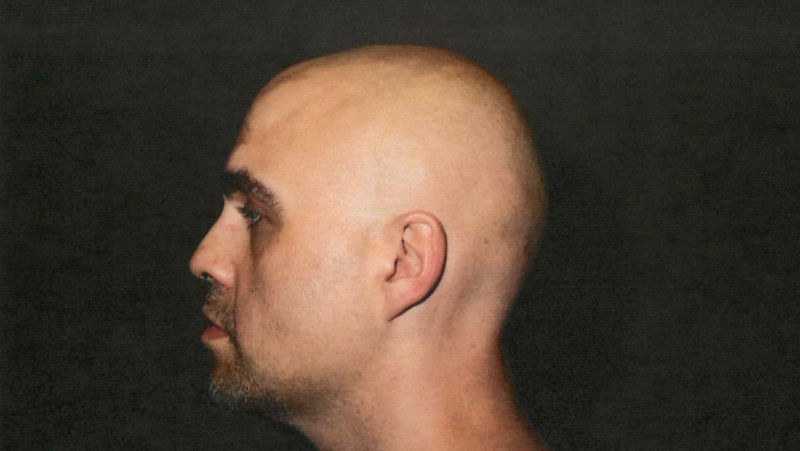

Mark Grant was 21-years-old when 13-year-old Derksen went missing in 1984. She was found dead weeks later.

Grant is charged with first degree murder and has pleaded not guilty.

At his trial on Friday, jurors heard from witnesses who knew Grant at the time. Two former friends of Grant were the first witnesses who testified about knowing him personally.

William Crockford testified that he lived on Talbot Avenue in an apartment attached to the Redi Mart where Derksen was seen on the day she disappeared.

Grant was a friend who would sometimes stay over at the apartment, where many people would often gather to drink at parties that would last for days, Crockford said.

"Usually, if we'd go to the bar, we'd invite the bar back," Crockford said in court.

Crockford testified that Grant was dating 14-year-old Audrey Manulak.

Manulak, whose last name is now Fontaine, was the next witness to testify Friday.

Fontaine said that she met Mark in 1984 when she was 14-years-old. She ran away from home three times that year and on one of those occasions she lived with Grant.

Fontaine could not recall the exact dates that she lived with Grant. However, she testified that it was while Grant had escaped from police custody in late 1984.

Crown attorney Brian Bell told the jury that Grant was in custody in 1984 and that he was taken to hospital and from there he walked away.

Fontaine testified that a while Grant was away from custody, he called her at her mother's home and they met up.

Then, she ran away and stayed with Grant for one or two nights in a place she described as "a hole in the ground."

Fontaine described the place they stayed as a concrete dugout near the train yards around Main Street and Higgens Avenue. She said it was underground, with a ladder that led down into a concrete space where Grant stayed and kept personal items, including a hotplate and a ghetto blaster.

After that, she stayed with him at his father's apartment for two weeks, she said.

Defence counsel Saul Simmonds asked Fontaine numerous questions about how much time she spent with Grant during that time.

Simmonds initially suggested that Fontaine and Grant were "inseparable" and "joined at the hip" while she was staying with him. Fontaine said that wasn't true and that Grant would leave her at his father's apartment to shop or socialize and she would leave the apartment without him as well.

Fontaine said both of them had a reason "not to get caught" because he had escaped from custody and she was a runaway, but they would both go out at times.

"He did not hide in the apartment," she said.

After extensive questioning, Fontaine eventually said she was probably only apart from Grant for short periods.

Earlier in the afternoon, the jury also heard from a witness who said that evidence at the centre of the case was stored in a cardboard box, possibly for more than a decade, before it was examined in 2001.

Sgt. John Burchill, an officer who worked on the case when it was reopened in 2001, testified about sending evidence to the RCMP to be analyzed for DNA using modern techniques.

That evidence included the twine that bound Derksen's wrists and ankles, as well as her jacket, jeans and some gum that was found at the shed where her bound was discovered.

Under cross examination, he testified that the twine was stored in a cardboard box in the Winnipeg Police Service evidence warehouse before it was sent to an RCMP lab where the DNA was analyzed.

In response to questions from defence lawyer Saul Simmonds, Burchill said he did not know exactly how the evidence came to be in the cardboard box or how many people had touched it before he sent it to the RCMP lab.

That DNA is a key aspect of the Crown's case, according to the Crown's opening statement.