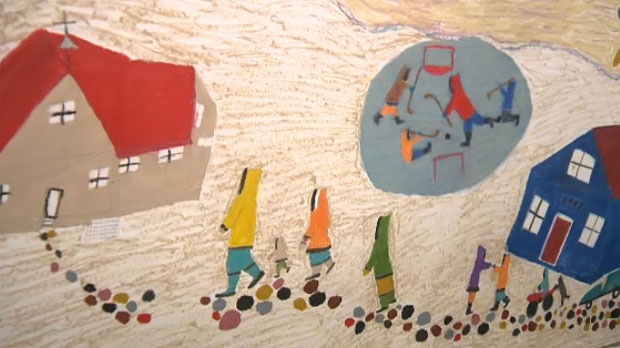

Winnipeg's art gallery is trying to carve out space to house what's billed as the world's largest public collection of Inuit art -- only a fraction of which is ever on display.

The gallery has plans to build a $60-million building for 13,000 pieces that include carvings, prints and drawings. The centre would include a climate-controlled "visible vault" of the collection, which the gallery says would be the first of its kind in North America and would offer education programs about the North.

Gallery director Stephen Borys said the 3,700-square-metre centre would be unique and would help bring the Arctic to the rest of Canada, considered the "deep south" to those in the North. The centre would raise the profile of "an art-making culture that, per-capita, is unparalleled in the world," Borys said.

"There are communities where 20 to 30 per cent of the community are art makers," he said Thursday.

"The art makers, who are behind these incredible objects, will have a platform, a voice and a way to communicate more of the land that they come from -- the land that very, very few Canadians ever get the chance to visit."

The gallery has a long way to go before shovels are in the ground. Although its funding request was recently turned down by the city, TD Bank announced a $500,000 donation Thursday to help fund an artist-in-residence and a printmaking studio.

It could be a few years before the centre becomes a reality, Borys said.

"It's something that will take a lot of money, a lot of support," he said. "There will be a building. We know it's going to happen."

Once built, the gallery will finally be able to display the pieces that make up half its permanent collection. Of the 13,000 pieces of Inuit art held in trust by the gallery, only about 100 are ever on public display at any one time.

There are also plans to store the collection digitally so it is internationally accessible.

The idea is welcomed by many in the Inuit community who would like to see a permanent place for Canadians to explore authentic Inuit culture. Fred Ford, head of the Manitoba Inuit Association, said art is an integral part of Inuit history, noting his people didn't have a written language until recently.

"This is how we've told our history and passed it on from generation to generation," he said. "These are our stories and this is our history."

Many people may not be aware of what goes into a carving, Ford added. The stone is harvested from the land, dug out of bedrock dozens of kilometres from home.

The fully displayed collection will provide a window on the way of life in the North for people around the world, Ford said.

"We want to tell the full story and really the reason behind the art."